Van Honthorst’s The Beheading of St. John the Baptist – a work immersed in darkness

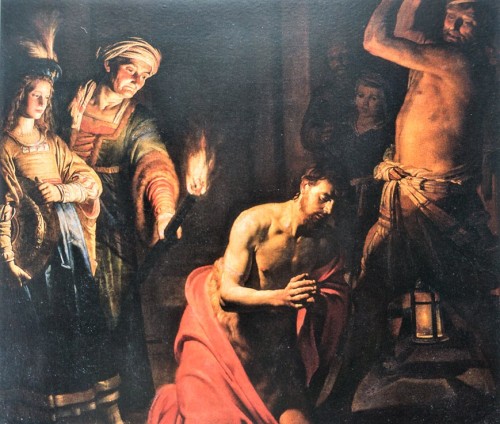

The Beheading of St. John, fragment, Gerard van Honthorst, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

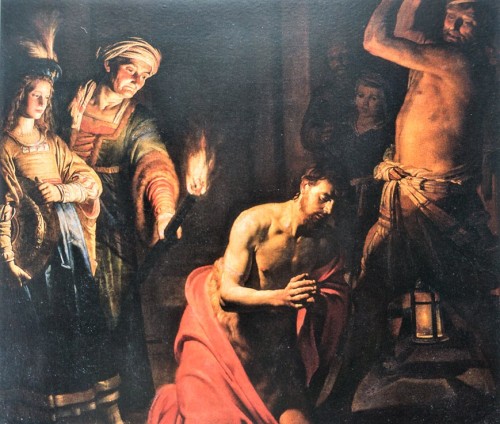

The Beheading of St. John, Gerard van Honthorst, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

The Beheading of St. John, fragment, Gerard van Honthorst, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

The Beheading of St. John, fragment, Gerard van Honthorst, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

The chapel of St. John the Baptist, The Beheading of St. John, Gerard van Honthorst, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

Gerard van Honthorst, The Beheading of St. John, fragment, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

Gerard van Honthorst, The Beheading of St. John, fragment, Church of Santa Maria della Scala

In the right nave of the Church of Santa Maria della Scala, there is a painting of a Dutch artist, who is considered one of the greatest imitators of Caravaggio. In undertaking such a work, the artist was aware of the challenge that he was faced with. The biggest of these was the monks who were in charge of the church – the Discalced Carmelites, who had in the past proven to be very demanding clients. This was previously experienced by two outstanding artists who had the opportunity to work for them.

In the right nave of the Church of Santa Maria della Scala, there is a painting of a Dutch artist, who is considered one of the greatest imitators of Caravaggio. In undertaking such a work, the artist was aware of the challenge that he was faced with. The biggest of these was the monks who were in charge of the church – the Discalced Carmelites, who had in the past proven to be very demanding clients. This was previously experienced by two outstanding artists who had the opportunity to work for them.

The Discalced Carmelites – an order established from a division (1594) of the friars into “discalced” and “calced” – in 1597 based on a papal bulla issued by Clement VIII were given an as-of-yet unfinished Church of Santa Maria della Scala on the Trastevere. Immediately after, a procedure was started to purchase the individual chapels inside the church, by rich donators, who desired to decorate them with paintings completed by artists they selected. And here is where problems started. When in 1606, Caravaggio's painting Death of the Virgin ordered by one of the chapel owners, was presented to the monks, they vehemently rejected it. The artist who was selected to complete a painting that would replace Merisi’s work – Carlo Saraceni, also faced problems. Only his second version, known enigmatically as Transitus Mariae was ultimately accepted by the Carmelites, despite the fact that artistically the painting was worse than the original one. However, the artistic level was not what interested the monks. The experiences of both painters had to be known to van Honthorst when in 1617 he signed a contract to complete a monumental altarpiece for another chapel in the church. He was aware that the painting could be neither iconographically nor morally controversial. However, it had to be both decorative as well as stimulating to devotion, and show the martyrdom of the chapel patron – St. John the Baptist. The chapel belonged to the majordomo of Cardinal Tolomeo Gallio – Giovanni Battista Longhi, who had died in 1610 and in a testament that he left behind ordered Maurizio Sanzo to execute his last will (including furnishing the chapel). However, since finances ran out, the works were delayed and it was not until seven years after the client's death that a contract was signed with a young Utrecht-born artist. That painting was most likely thoroughly discussed with the monks so that it would not share the fate of the canvases of Caravaggio and Saraceni. However, its author was faced with a difficult decision: how to show the scene of the death of St. John in a way, so that the figure of Salome – the second main protagonist of the event – would be visible but would not be in the foreground of the scene. And thus, calling upon the Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), van Honthorst presented the scene of the beheading of St. John, after he dared to criticize the marriage of the ruler of Judea, Herod Antipas with Herodias. Previously she was the wife of Herod Philip, with whom she had a daughter named Salome. Abandoning her first husband she married his brother, which according to tradition and Jewish law could not take place. John, who was popular among the Jews, and by some, was considered a prophet, ran afoul of Herodias and raised the king's fears. And here is where Salome enters the stage, dancing at the birthday feast of her stepfather, while he – enchanted by her beauty and charm – declares that he would fulfill her utmost desire. Without giving it a second thought Salome demands the head of John, who was hated by her mother. In the painting, the author shows the next chapter in this story, which takes place in the dungeon. In complete darkness, the executioner takes a swing to behead the kneeling John, while the woman standing next to him, holds a lit torch, and the girl standing beside her in a festive dress holds a platter awaiting the convict's head, which will soon fall upon it. In the background, we can also see two figures hidden in the darkness: a man and a woman who are witnessing the scene. Whether it is the royal couple is difficult to say. In the upper part of the painting, we will also see an angel who is carrying a wreath of martyrdom for John.

Undoubtedly the clients could be satisfied – van Honthorst created both a poignant and decorative work, based on not only luminous but also emotional contrasts. The calmness of John focused on prayer is responded to by the executioner swinging his sword. The face of the old servant with plebeian features illuminated by a strong light contrasts with the face of a young, pretty girl, who however is bereft of any kind of erotic charms that were so willingly used by other painters at that time. The martyrdom of St. John takes place in silence, without excessive expression, that can only be seen on the flushed faces of the women. This is typical of the work of van Honthorst, who in his paintings attempted to tone down the emotions of the protagonists, silence the dramatism of the scenes, focusing on the value of light and composition. And that is the case in this painting. The center of the scene remains empty, while the bodies surrounding this void are partially illuminated – it is as if the glow of truth descended upon them at the time of the saint's death.

That, which was used by the painter to amaze us, was not only the well-thought-out composition based on opposites but also the magnificent color scheme. It is enough to look upon the colorful dresses of the women, their shining cloaks, glowing golden trimming, the thickness of the fur at the endings of the sleeves of the dress, or the delicate feathers adorning Salome's head. The use of ultramarine to paint Salome's dress, a pigment that was extremely expensive and very valued was to ennoble and grant additional splendor to the painting. But that was not all. Van Honthorst exhibited all of his talents, directly introducing artificial light into the painting. It illuminates the interior and the individual parts of the bodies of the people seemingly found on a stage, creating an incredible mood. The torch held by the old servant brings the faces of the women, the nude torso of John the Baptist and his executioner as well as the angel's arm out of the darkness, while the lantern found in the background – the two barely visible figures. Like no one before him the painter brought figures out of the darkness at the same time not losing any intensity of colors. There was a reason that in Rome he was known as Gherardo delle Notti since his nocturnes virtually enslaved such consummate collectors as the Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani. His collection boasted several paintings completed by the Utrechtian, including Christ Before the High Priest painted the very same year, that enjoyed great esteem and is presently located in London (The National Gallery. It is also considered the greatest work of the artist’s Roman period. In that scene only one candle illuminates the figures of the heroes, bestowing a very cozy yet poignant mood upon the scene.

When we look at the painting The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, still today found in its original destination, it is impossible not to think about another artist who, next to Caravaggio, will become a pillar of the art of the Seicento period – Rembrandt. And we would not exaggerate in saying that the art of van Honthorst is a bridge connecting these two ingenious painters.

The Beheading of St. John, Gerard van Honthorst, 1617–1618, oil on canvas, 345 x 215 cm, Church of Santa Maria della Scala